ATHLETE RACE AND TRAINING BLOG

A place to report, share and learn from fellow athletes

2022 Boston Marathon Race Recap

Race Recap from the 126th Boston Marathon on April 18th, 2022 -- I did my best to put this race into words but sometimes capturing what happens during these moments is unexplainable. Here's my best shot...

Heading into the race I had felt really strong. I didn't set a time goal but instead, I set some small micro-goals to hit.

1) Run my last mile as my fastest mile.

2) Find a nutrition strategy that worked for me.

3) Have f****** fun, and soak up this historic race.

Pre-Race

I started out with the usual race-day jitters. Waking up at 5 AM, we had about 5 hours before we hit the start line. I did my best to eat on a jittery stomach, listened to some Dermot Kennedy to calm me down, had some coffee, went potty, had electrolytes, two bagels, and was out the door to the buses.

The bus ride was about 50 mins out to Hopkinton, and from there we had about an hour to kill before we loaded into the coral. I ate a PBJ, drank some G1M Sport, and then we started to line up in our corals. We walked down from the Athletes Village to the start line and it was time to rock.

The national anthem played, two F-15s flew over - I teared up. This is what makes race day so special. It's hard to put into words what this feels like. I looked at Hanna, said "time to have some fun, let's do this" and boom, the gun went off.

The Start

Mile 1 was an absolute cluster-fest. People were everywhere, bumping each other, and a few people tripped. It was crowded & very hard to get into a rhythm. We snuck off to the right side and found some room to run in.

Miles 2-10 I felt like I was on cruise control. One foot in front of another, controlled breathing, just pure bliss running. Miles 3/4 @ 6:21 pace & Mile 5/6 @ 6:22 pace. We stuck to our plan of mid 6:20's pace and didn't let the downhills suck us into running faster than our plan. A teammate told us that if you hit it hard, your quads will be destroyed by Mile 10, so we listened (they were still hurting, lol...)

For nutrition throughout, we were sipping on our run bottles which had 40g of carbs, and 1000mg of sodium. For gels, it was one Huma Gel every 5 Miles. Then I would grab a cup of water at the aid station to rinse it down (harder than it sounds) and then grab another cup to throw on my neck/back to cool me down. 54 degrees and sunny had me sweating more than usual. The plan was solid, and we kept to it. The Huma gels helped sustain the energy we needed.

Miles 10-16 were the same thing. We kept it at our planned pace. Miles 10/11 @ 6:24 -- Miles 12/13 @ 6:21. Everything felt pretty strong. I kept telling myself "stick to the plan, stick to the plan, soak it all up!" -- knowing the hardest part was approaching we had to get ready for it. After a big downhill at Mile 16 at 6:18 pace - it was time for the biggest 4 miles of the race.

Boston is known for the Heartbreak Hill but it's really a collection of them starting at mile 17, ending with the biggest one at Heartbreak Hill (Mile 21) -- I told myself I can do anything for 4 miles, just stick to the plan! This is actually when my quads got a little bit of a break, and it was time to use the hammies more. Kept it anywhere from 6:25 to 6:35 for the first 3 miles and then at Mile 21 (Heartbreak) we slowed to a 6:43 pace. Once I hit the top of the hill, my legs were screaming, and we hit a big downhill right after which did not help. I knew there was work to be done. 5 more miles!!! Heading into the biggest crowd, and the city of Boston.

We got right back on track at Mile 22-24 anywhere from 6:23-6:26 pace. I knew we had this in us after practicing so many big hills during our prep. You have to put yourself in the same challenging situations to be able to overcome them come race day. So here it was, back in the groove, I finished the last few sips of my bottle, grabbed a water cup and threw it on my neck, and was ready to finish. Onto my favorite mile.

Mile 25 I dug deep into the cookie jar. I used past experiences to fuel this. Something snapped in me and knew it was time to empty the tank. They had a big sign at Mile 25.2 with "1 Mile to Go" -- I looked back at Hanna and she said "Go, you got this."

Mile 25.2-26.2 at a 5:57 pace -- my fastest mile of the day. I hit another gear that I have never experienced in any of my races. Something just hit me, and it was time to leave it all out there. Step after step, I kept telling myself, "You are not out of the fight, push."

I took the right, and then a quick left to get us onto Boylston St where I could see the finish line. The crowd here was on another level, I soaked it all in, every single second. 200 yards out, I hit another few big strides - wanting to leave every ounce of it out there.

I hit the blue & yellow finish line and everything felt like it clicked.

02:49:06 - a new 26.22 PR by over 9 minutes, in less than 6 months.

Final Thoughts

Heading into this race I knew the prep had gone to plan and it was shaping up to be a big day. We hit big milestones throughout the last 3.5 months that I knew would help us on race day, thanks to the team at the Endurance Drive.

I hit the 3 goals that I set for myself and the biggest one was to have fun out there. That doesn't mean every second of the race was fun. There were times it sucked, my legs felt like glass, you question if you have it in you. It's digging deep to find the new measures that will take you out of those places. It's being surrounded by 30,000 other runners who are out there for the same reason, to better themselves.

This race was truly amazing to be a part of. I have so many good memories from start to finish.

Thank you to everyone who reached out before the race, during, and after. Your support means the world. I love this sport, and the people it has connected me with.

Time to enjoy this, and get ready for the tri season.

Final St. George Prep Thoughts

Three weeks from today is the Ironman World Championships in St. George, Utah. It’s crazy how fast the months and months of high volume training—most of it in the dead of winter in New England—have ticked by. The last few weeks before an Ironman event always feature a steady decline in volume, and with that, an increase in the amount of headspace I have to detach from the training grind and reflect on how I feel about my prep and the race itself. This post is about those thoughts.

For some context, Jim and I traveled to St. George last weekend for our final big race simulation (a 112-mile ride on the bike course and 13.1-mile run on the run course on Day 1, and another 13.1-mile run on Day 2). A full recap of that event is a story for another blog post, but in a nutshell, it was a really tough day. We battled extreme environmental conditions (heat, sun, wind, climbing, altitude) and some unexpected logistical challenges with navigation and road closures. The day hit an especially low point when we started the long highway descent from Veyo and encountered headwinds and crosswinds that shook my bike and made me feel like I was going to flip over. We then entered a construction zone that routed all of the cars in the right lane onto the shoulder we were riding on, and we were immediately surrounded with impatient drivers trying to pass us with no room.

At this point, my heart rate was skyrocketing despite going downhill, and I started to struggle to breathe. Within minutes, I realized I was actually having a panic attack. I was able to pull over into some bushes and get off the road, but I then spent 15 minutes hyperventilating, sobbing, and trying not to throw up. Jim eventually got me to calm down, but our day was essentially over at that point. We soft-pedaled back into town and skipped the Snow Canyon climb, then immediately began to feel heat stroke coming on in the 90F temps once we started our run. We turned around after a few miles and called it.

While scary, the whole experience wouldn’t have been all that bad if it were a fluke—a minor deviation from my maximally consistent approach to training. Unfortunately, that hasn’t entirely been the case. Since last weekend, I have started to feel the same panic symptoms set in during many of my workouts. Breathing faster for perfectly normal reasons (like intervals, even when swimming or running) freaks me out. Cars and winds make it worse, and I am not comfortable at all in the aero position on my bike because I can’t have my hands on the brakes. Worst of all, earlier this week we found out some devastating news that has made it hard to want to bike at all: on the same day as our race simulation, two cyclists riding in the bike lane on the St. George course were killed by someone driving on drugs about an hour after we had passed the spot they were hit.

I’ve been trying to process how I feel about returning to St. George to race. Truthfully, I’m not exactly sure what triggered these changes in my mindset. Winds, heat, traffic, elevation, and big volume rides can certainly be stressful, but I’ve experienced all of those things before. As Jim remarked, “We’ve done a lot of crazy shit, so it’s interesting that this was the first time I’ve seen you crack.” Ultimately, I think it’s a combination of environmental factors and a deeper realization that this race is going to be harder than any race I’ve ever done before. Some of the goals I started dreaming about while riding in the Vermont pain cave in February may not be realistic on this course. Even making it to the finish line in one piece—both physically and mentally—will be a challenge. After all of the hard work that has gone into prepping for this race, that’s a scary thought.

Even so, being open about how I am feeling has helped. My network of friends, family, and my endurance crew has been so supportive. Here are five mantras that my people have shared in just the past week that have pushed me out the door for those final sessions:

Our bodies like to be alive and have great protection mechanisms, so this is a good sign that everything is working properly.

If it’s hard for you (i.e. heat, wind, hills, etc.), it’s hard for everyone.

Be gentle, and give yourself grace.

The hay is in the barn.

If you need to, talk to someone.

I’m not sure how the next few weeks will feel, but I’m determined to keep getting out there. I’m excited to keep you posted on how this final chapter of the St. George journey goes. And I’m taking recs for more mantras. :)

–Coach Katie

2021 IRONMAN 70.3 Timberman Race Report -- Ben Levesque

Timberman 70.3 Half-Ironman in Laconia, NH was my first triathlon experience. With about 13 weeks of training I knew I would be able to cross the finish line if I relied on lessons learned throughout the summer. In late May, I set a goal of a sub-7 hour half-ironman under three broad assumptions—a bad swim, an average 15 mph bike, and an average 10’ 30” per mile run. On race day, I predicted a 7:30:00 overall time, and I aimed for a 3:30:00 on the bike. Here’s a recap:

Swim: The swim course on Opechee Lake had three red turning buoys, with four yellow “outbound” buoys and four orange “return” buoys for athletes to follow. On the morning of the race, the water temp. was 75.4° F, meaning that the race was swimsuit legal according to the athlete guide. This meant that athletes could wear a wetsuit and maintain their eligibility for age-group awards and/or world championship slots. I decided to wear a wetsuit and lined up with the 50-55 minute projected swim finish group.

The swim was my greatest concern because I lacked a metric for my race swim pace. Though I’d been exclusively training in open water all summer, the Garmin Forerunner 35 never produced usable data. I settled my nerves by talking with a few competitors as we waited for the waves of athletes ahead of us to start. For many athletes I spoke to it was their first half-ironman, and for a few their first triathlon. At 7:18 am, I entered the water. I spent the first 20 mins. finding my rhythm. At some point between the first and second turning buoy, I took a second to look at the other athletes and I decided that I was raising my head too much when I went to breathe. I adjusted my form and the benefit was instant; I felt faster and more relaxed. I exited the swim with a smile, and was surprised to see Dartmouth Triathlon coach Jeff Reed cheering (alongside Coach Jim) as I headed to T1.

Bike: I felt most prepared for the bike. I’d spent the summer adding miles on the bike and I’d completed several long-rides beyond 56 miles, so I had no doubt I could complete the distance from a training standpoint. I hadn’t been able to preview the course, but a quick review of the athlete guide (and a few conversations with teammates) informed me that the first 35 miles were relatively flat and the next 21 miles had challenging ascents.

I saw several teammates along the course, including Coach Katie Clayton and London (on their way back from the turnaround), Vaishnavi, and Evelyn. Throughout the first 2.5 hrs. I fuelled well (water/Gatorade every 30 mins., gel/bloks/Clif bar every 60 mins.) and felt strong. The ascents in the latter half of the course felt familiar having cycled similar ascents in New Hampshire and back home in Maine. Three-quarters of the way up the final ascent (about 3:04:00 in the bike), I dropped chain. I hopped off the saddle for a quick fix and proceeded to power through the descents. Checking my watch, I knew I would be close to 3:30:00 if I pushed myself through to T2. I completed the segment with an official time of 3:30:11.

Run: The run course consisted of two ~6 mi. loops around Opechee Lake, followed by a straight downhill to the finish. I used the first loop to orient myself to the run, and simply focused on reaching “the next aid station” (mentally, every aid station became “the next aid station”) for water or Gatorade.

Rather than my regimented nutrition on the bike, I lost a sense of fuelling during the run. Other than the banana I strategically picked up around mile 6, I was unfocused with my nutrition—this is something I plan to improve for the next race. Nevertheless, the miles passed without much trouble. By 6.5 miles I was bolstered by the knowledge that I would complete a half-ironman (because I couldn’t just run half the distance). Around mile 12, my right calf cramped (for the first time in a racing or training environment) as I descended into Laconia, though the pain was manageable; I smiled as I heard athletes being announced at the line less than a mile away.

My teammates were there cheering me on and it felt like the perfect finish. In the end, I completed the event in 6:58:48 (49:04 swim, 3:30:11 bike, 2:24:41 run).

Final Thoughts: Adventurer Mark Beaumont said that in his first circumnavigation of the world (by bike) in 2008, he came within eight hours of his planned duration (with a total time of 194 days and 7 hours). He learned how closely his goals were related to his actual performance. I was shocked by how close my performance came to my goals and estimates—after seven hours, I hit my target half-ironman within 1’ 12” and my target bike within 11.” Given the connection between goals and race performance, I plan to set informed targets for the swim and run in future races.

- Ben Levesque

(Ben is a member of the Dartmouth Triathlon Club and class of 2024)

Dartmouth Triathlon Club IRONMAN Timberman 70.3 finishers.

Ben crosses the finish line at Timberman 70.3, his first triathlon!

2021 IRONMAN 70.3 Timberman Race Report

IRONMAN Timberman 70.3 Race Report

IRONMAN Timberman 70.3 is in the books! After a disappointing post-pandemic season opener at the Patriot Half in June, I went into this race nervous that my lack of a consistent approach to 70.3 training and nomadic lifestyle over the past year and a half would make it difficult to perform well at the half distance. With great support and advice from Jim, I made it my goal to toughen my mental game and race “smarter, not harder.” I’m excited to report that I was super happy with the result: 2nd in my new age group (F25-29) with no major low points and a strong finish! Here’s a recap of the day:

Swim: The Timberman swim is a single loop with three turn buoys in Opechee Lake, a small lake near Winnipesaukee in Laconia, NH. With Hurricane Henri in the forecast for the mid-Atlantic, the water was a little choppy but definitely could have been worse. Endurance Drive athlete and my Maine-based training partner Ella and I lined up at the end of the 30-33 minute projected swim finish group, following Jim’s advice to seed ahead of where you think you will swim because nearly everyone overestimates their swim time. Following a time trial start, we were in the water by 7:04 am and onto the course.

Two big mistakes I made at Patriot were 1) going out too hard in the swim and 2) not properly warming up beforehand. Luckily, Ella and I had time for a brief swim warmup before the gun went off, and as soon as we started swimming I focused on resisting the urge to swim too hard. The TT start and early seeding made the water less chaotic than a mass start, so I settled into a rhythm quickly and found someone to draft behind with good sighting skills and a strong kick. Shout out to that mystery woman with a BlueSeventy wetsuit for making my swim mostly stress-free! I stayed behind BlueSeventy around all three turns, and then picked up the pace a little bit on the way back in because I felt really relaxed and in control of my HR. I cruised into the swim finish and was surprised to see a better time than Patriot with much less effort expended (smarter not harder FTW!). I stayed in control and had time to say a quick hi to Jim and the other Dartmouth triathlon coach, Jeff, as I jogged into T1.

Bike: At Patriot, my HR was extremely high for the first hour of the bike because I had overcooked the swim and was still trying to put out HIM watts. At Timberman, I knew that I needed to not worry about watts and focus more on keeping HR in control. The bike course is roughly 35 miles on a pretty flat out-and-back (slightly downhill with a tailwind on the out, slightly uphill with a headwind coming back), and then about 15 miles of punchy, steep hills before another 6 miles descending into town. I knew that I could get a lot of free miles in the first hour, so I held back the watts and focused on staying in aero at a moderate effort. My HR was high initially but came down as I cruised the flats, and I immediately started hydrating and fueling to set myself up for a strong finish.

There was a substantial headwind once I hit the turnaround, but at that point I was warmed up enough to push HIM goal watts without spiking the HR. I saw Ella and Dartmouth Triathlon athletes Evelyn, Ben, Katie W., and Abbi as I headed back toward the hills and got a morale boost from seeing familiar faces. Before I knew it, I was at mile 35 and ready to tackle the “fun” section of the course. Ella and I had driven that section the day before and we were both worried about how challenging it would be, but I soon realized that all of my training in VT/NH/ME for the last year and a half had been outstanding preparation for terrain just like this. The 11-30 cassette I (well, Jim) installed on Betty, my new Canyon Speedmax CF 8.0 SL, could easily handle the steeps, and I started passing people left and right while still feeling in control. My only complaint at that point was that I felt a little nauseous and couldn’t take in more blocks or bars, but I had enough carbs via Skratch to be nutritionally topped off even if I wasn’t taking in solid food, and I forced myself to keep sipping as I climbed.

After the final steep kicker, I enjoyed the descent back into town, although I got slightly held up by a race official on a motorcycle who wouldn’t move over for me to pass him. I’m not sure what you’re supposed to do about race etiquette in that situation, but I didn’t want to risk a visit to the penalty tent so I ended up braking on the downhill. Even so, I was thrilled with my bike split as I came back into T2 considering how hilly the last section was, and even happier that I had continued to race smart. I threw my shoes, visor, and race belt on quickly, and then it was time to run.

Run: Jim, our social media guru Colleen, Jeff, and a whole bunch of Dartmouth supporters were stationed directly out of T1, and it was so fun to hear them cheering as I began the run. I was also feeling great and the nausea had gone away, so I clocked a few fast miles that felt effortless. The run course features two hilly loops around the lake, a final climb, and then about two and a half miles downhill into the finish. Jim had reminded us that racing smart would involve running “softly” (easy, low effort) on the uphills and striding out to pick up the pace on the downhills, so I did my best to modify my pace to match the terrain. I dumped water and ice on my head and down my shirt to stay cool at every aid station, and fueled with SIS gels and a little bit of coke and Gatorade.

At the end of the first run loop, I passed our cheer squad again and realized I was right behind Ella. Jim told us that we were 2nd and 3rd in our age group, so I knew that if we each held consistent paces we would end up on the podium. I moved up to second by mile six and tried hard to stay in control, although my legs were getting fatigued and my GI system was not doing great. I made the strategic decision to spend ~40 seconds in a porta potty at mile 9 because I wanted to finish the last stretch strong, and after that I hit a pretty strong second wind. I ran softly but consistently up the last incline, saw Jim for one more morale boost, and then clocked my two fastest miles of the day into the finish as the rain began to come down. I crossed the line in 5:08:10 (34:46 swim, 2:48:49 bike, 1:39:44 run) and got to share post-race hugs with tons of the Endurance Drive and Dartmouth Triathlon crew.

Some final thoughts: As Jim and anyone who knows me even remotely well can probably tell you, I was not happy after Patriot (although my disappointment about that race has honestly become something we all laugh about now). There were dozens of variables that differed between that day and Timberman: weather, preparation, course, spectator support, fellow racers, even menstrual cycle phase (which matters! Stay tuned for a blog post on that sometime soon). That said, I think the biggest key to success for me was racing smarter (not harder) and being patient, which led to a much more enjoyable race and a much stronger result. I regained a lot of confidence in my racing ability after it had been shaken, and I’m super excited to see what I can accomplish with a more consistent 2022 season! Next up: two weeks of hiking in Switzerland for my honeymoon, then Lake Sunapee Olympic Tri on September 18th for fun, and then IRONMAN St. George in May 2022!

Coach Katie Clayton 2nd in AG at IRONMAN Timberman 70.3

Katie, Jim & Ella relax after a long day of racing and coaching The Endurance Drive & the Dartmouth Triathlon Club

2021 IRONMAN Lake Placid Race Report -- E. Thomas

Ironman Lake Placid 2021 -- Race Report by E. Thomas

Race information

What? Ironman Lake Placid

When? July 25, 2021

How far? 140.6 Miles

Where? Lake Placid, NY

Finish time: ~13:30

Goals

Goal A: Finish (✔)

Goal B: Finish (✔)

Goal C: Finish (✔)

Brief Preamble

I’m writing this selfishly to crystalize the experience for myself, but I’ve gotten a lot of value from reading other folks’ race reports, so I decided to share publicly. I’ll start out by saying that I don't have a ton endurance experience, and this isn’t a heroic tale of a Kona-qualifying race, but of the average joe trying to complete a full Ironman so he can brag to his friends and family.

I started running two years ago when a couple of buddies and I decided to do a “couch to marathon”. I quickly caught the endurance bug and wanted to try out triathlon, so I signed up for a half Ironman in 2020, which was cancelled. I ultimately decided to just full send a full Ironman to short circuit the process, since I knew I’d eventually want to tick that off the list. I did complete a half Ironman a few months before Lake Placid, but mostly just to orient myself with how to do a triathlon.

Pre-race

They say the sleep two nights before the race is the most important, so if you don’t get a wink the night before, it won’t blow up your day. Well, this notion was top of mind for me and I’d say about three to four nights out, my brain started whispering to me at night, “hey buddy, wouldn’t it suck if you not only couldn’t sleep two out, but three nights out as well!!”. I’d eventually get some shut eye, but often with the assistance of some over-the-counter aid, which I try to reserve for emergencies. Funny enough, I was able to sleep decently the night before.

I was surprisingly Zen the morning of. I woke up, stuffed a bunch of calories and electrolytes down my gullet, and patiently waited for my drivers (aka mom and girlfriend) to get up and take me down to the race start. It was 4:00am and they wouldn’t be up for another hour…

Fast forward a bit, I’m standing on the “sandy beach” of the lake swim start with what feels like thousands of other swimmers and spectators cheering us on. There’s a soft drizzle, music is blasting, and the Ironman announcer guy is walking around giving everyone high-fives. Zen turns to nerves, which turns to excitement, to nerves, to excitement, to Zen. The spin cycle repeats.

Swim

The swim was a big unknown for me as I had only completed a half Ironman distance OWS prior to doing the full. I live in NYC and was confined to mind-numbing laps in the pool as the area is not necessarily known for its pristine open water.

As a novice swimmer, I tried to appropriately seed myself with folks that would be going the same pace (although I’ve heard time and time again to bump yourself up to a faster time because everyone overestimates what they can do). I lined up with the 1:50 sign, which I thought meant that this group would be doing 1:50min/100yds. It turns out that this sign meant finish the full swim in an hour and 50 minutes, which is a much slower pace. I was one of the last people to get into the water.

At the start of the swim, I was in hand-to-hand combat trying to get around people that were doggy paddling, doing the breaststroke, etc. Eventually I got onto the cable, the crowd spread out, I unplugged my brain and was at the finish line before I knew it. There wasn’t much more to it than that. They say that the swim is the mandatory path you need to take to get to the real race start, which seemed to be the case.

Bike

The goal was to finish, not to go for gold, so I took my sweet time transitioning from the swim to the bike. Lake Placid has a gnarly bike and run course so I wanted to save every match that I had.

On the first hill out of town, I saw a bigger guy on a nice bike absolutely grinding at a low cadence. He told me that his electronic shifting had run out of battery and he was stuck in one of his hardest gears at mile 3 of 112 on a course with 7K feet of elevation gain. Poor guy. I wonder how he made out.

I consider the bike one of my “strong” suits, but the Lake Placid course has a special way of humbling all who test their luck on it. I was confident going in and I knew what to expect as I had pre-ridden the course with my coach and a few other people that I now consider good friends. My nutrition was dialed, I was planning to take in ~80 grams of carbs an hour through liquids and solids. However, about 30 miles into the race my legs started to feel pretty flat and my GI system was starting to show signs of distress. I’m not sure why this happened, maybe I was psyching myself out by constantly thinking about running an effing marathon after the bike. 150 watts felt hard when I knew I could hold 200+ watts for 6 hours.

But I had prepared for this. Testing your mettle is one of the beautiful things about endurance sports. I quickly shifted into a tunnel-vision headspace and focused on just getting to the next aid station, one pedal stroke at a time. This happened much sooner in the race than I would’ve liked, but it is what it is, and I was going to finish the damn race no matter what.

It’s a very challenging bike course and people were getting popped left and right. The 10-mile climb back into town (into what felt like a never-ending headwind) was a character builder, especially on the second loop after having biked 100 miles. But if you just keep pedaling, eventually you get to where you need to go. Special shout-out to the spectators that were lined up on basically the entire 56-mile loop, cheering everyone on.

Run

The run course. This is where the big bucks are made. I could not believe I was about to run a marathon after having just spent over an hour in the water and seven hours on the bike. But I paid to do this…

After over 15 minutes in transition, I laced up my sneakers and headed off into town. My legs felt surprisingly good and I had a little pep in my step. That little pep turned into a big pep when I saw my family and girlfriend right out of the gate cheering me on. As I got further into town, the electricity skyrocketed. Spectators were going nuts. Lake Placid really is a special race venue.

I continued to run well and was sticking to my plan of drinking a water and Gatorade at every aid station, along with taking in a gel every three. About 10 or so miles in, I started to really feel the culmination of the day’s activities (in both my legs and my gut), and I once again shifted to the tunnel vision survival mode of chipping away one mile at a time. But I have spent a lot of time in this pain cave and have learned to enjoy it. I knew what to do - one foot in front of the other, one mile at a time.

Eventually my legs were in searing pain and my gut simply could not take in anything more. I had reached circle seven of Dante’s Inferno, but still had 8 miles to go. It seemed like most people were walking at this point, and it was really tempting to do so myself, but the more I walked the longer I’d be out on the course – it wasn’t an option (except for going up hills). People were limping, people were cramping, some people were straight up laying on the road – but they all kept moving forward and it was incredibly inspiring. Pretty deep into the marathon, I was chatting with this older lady who said she was just starting her first loop and still had 20 miles to go, but she was determined to finish before the cutoff and there’s nothing that would stop her. It’s moments in time like this that stick with you for life.

In true Lake Placid style, at the very end of the run, they make you run up this big hill before hooking a left to get to the red-carpet finish line (thanks!). I was coming into the finish and it felt like thousands of people were cheering for me. I was getting misty eyed as I felt the culmination of many months of hard work and sacrifice finally come to an end. And then some random dude sprinted past me with 5ft to go before the finish, abruptly shaking me out of my self-indulgent moment…

Concluding Thoughts

This event will probably go down as a top life experience. There’s something special about testing the limits of your mind and body, as bonkers as it sounds. It’s fundamentally changed my outlook on what’s possible, which has permeated most aspects of my life. I feel blessed to have had the opportunity to do something like this and to have had the world-class support from my loved ones and coach (shout-out to the Endurance Drive!).

I think I’d do another one, but maybe not for a while. It’s an all-consuming commitment, but it turned out to be well worth it.

From Swimmer to Triathlete -- Chris Klein

From Swimmer to Triathlete

By: Chris Klein aka Mr. Klein

I was a competitive swimmer for a decade before I started racing triathlons. Earlier in my triathlon career, the swim was my time to perform and the bike and runs legs were a relentless (and sometimes unsuccessful) battle to hold on to the lead. Since working with Jim and joining the Endurance Drive, I’ve learned how to better utilize my strength as a swimmer to give me a competitive advantage in triathlon.

Time-wise, the swim in a triathlon is the least important leg. The difference between a good swim and a bad swim in an IRONMAN event is a matter of minutes, whereas a bad run could exceed an hour slower than your goal race pace. But that doesn’t mean the swim isn’t important. In fact, a solid swim can set you up for a successful race.

From a swimmer’s perspective, the goal of the swim is simple: establish control of the race from the starting line and exit T1 feeling fresh enough to execute a solid race strategy. However, swimmers’ advantages are not limited to their lead coming into T1; competitive swimmers understand how to race comfortably in what is arguably the most chaotic leg of the triathlon. Their mental fortitude developed after thousands-upon-thousands of laps transitions seamlessly into their training mentality.

Below are some of the ways I’ve incorporated my swimming background into my training and racing:

We know how to pace! Recently, I posted one of my swim workouts on Strava which involved repeat 100-yard intervals holding a pace which decreased 2.5 seconds per set. One of my training partners asked if I could seriously pace my swims that precisely, to which I responded: yes! A benefit of the countless yards involved with competitive swim training is body awareness. In the same way that a trained marathoner correlates race paces to sheer seconds, or how a trained cyclist knows the difference between sweet spot and threshold efforts, competitive swimmers know how to use their pacing to effectively train and race for certain distances. From Olympic-distance to IRONMAN, triathlon swimming is distance swimming -- a sport where consistency is key. It’s crucial to figure out your race pace, train at those intervals, and learn how to balance speed and comfort. This is something I’ve been able to apply to not just swimming, but the other two legs of the triathlon as well.

A swimmer’s goal is to get out of the water prepared to race a duathlon. Jim jokes to me that “swimmers gonna swim,” and he’s right -- trained swimmers should exit the water in the front of the pack. Very rarely in a triathlon, however, will the swim be won by a single racer. Drafting strategies encourage pack swimming and larger swim finishes. The real difference between trained swimmers and the rest of the field comes down to energy. A weak or mid-level swimmer could use all of their energy to stay towards the front of an Olympic-distance swim, but then they run the risk of using all of their energy staying on the stronger swimmers’ feet. Conversely, swimmers can race an aggressive and controlled swim and exit the water in the lead or front of the pack, and still feel energized enough to execute a strong bike and run (hence, a duathlon). Runners and cyclists need to learn how to swim, and then they need to learn how to swim fast. Swimmers can focus on the bike and run, reserve their energy, and still swim faster than their opponents who prefer land.

We are comfortable in our own heads. There are very few distractions in pool swimming. Music doesn’t carry well underwater, and a long black line is often the only visual stimulation. Swimmers are used to training within their own heads and using thoughts, songs, and counting to get them to the next interval. They don’t rely on external stimuli for pacing, encouragement, or distraction. Triathlon training, especially in the Northeast where cold weather encourages indoor training many months of the year, requires self-discipline. Secluded race courses (such as the River Road stretch of IRONMAN Lake Placid or the Queen K at the IRONMAN World Championships) leave athletes with hours of silence save labored breathing and shuffling footsteps. The static environment of a pool trains swimmers to survive the mental aspect of triathlon, which leads me to my final point...

Swimmers embrace the pain cave. When done right, a swim workout can punish the body mentally, physically, and emotionally. At my peak, I was training somewhere between 30,000 – 40,000+ yards a week. Training trips and twice-a-day distance workouts taught me that our bodies have a breaking point, but I’ve found that we often back down before we reach that point. Swimmers, having reached that point and continued swimming for another 1,500 yards, understand how to balance pure, raw physical exhaustion with enough mental strength to push their bodies through a workout. This skill directly translates to the bike and the run. 10 sweet spot intervals on the bike? Let’s go! A long threshold run today? Bring it on! When their bodies are about to give up, swimmers are prepared to push their limits further, and they embrace the pain with smiles on their faces.

A race cannot be won in the swim, but it sure can be lost. Whether they deplete their energy too early or fall too far back in the pack, untrained swimmers are vulnerable opponents for athletes with a swimming background. When swimmers use their skill set correctly and incorporate their learned work ethic into their training, the competitive advantage gained might be enough to dolphin-kick right onto the podium.

Part 2: The Female Endurance Athlete

In the second installment of our three-part series on female endurance athletes, I’d like to talk about something that all athletes like to pretend doesn’t exist until it stops them in their tracks: injury. While sports injuries are absolutely not a women-only problem, there are certain aspects of female physiology that make us more prone to imbalances that, when ignored, can lead to ACL tears, IT band syndrome, patellofemoral syndrome, and more.

How do women differ from men in our propensity to certain sports injuries? For starters, women’s muscle stretch reflex changes over the course of the menstrual cycle, which means that our connective tissues are less flexible at certain hormone levels than others. Second, because we are evolutionarily designed to bear children, women’s hips are naturally wider than men’s, which means that we are more likely to run with a knock-kneed gait and excessively overpronate. Third, women are anatomically smaller than men, which means that our joints and muscles are more compact and can create excessive friction when they rub together during activity. Finally, because inadequate estrogen due to menstrual cycle imbalances is a common problem among female athletes, low bone density tends to be more common among women than men, and this leads to a higher instance of stress fractures (see Part 1 in this series for more details on how to reduce the occurrence of stress fractures in female athletes).

Does all of this mean that we should give up on participating in sports? Of course not! But as women, we need to take extra care to make sure that we work on core strength development and mobility work that can counteract the anatomical traits that may be working against us. Here is a list of things you can do to help prevent some of the most common injuries in female endurance athletes:

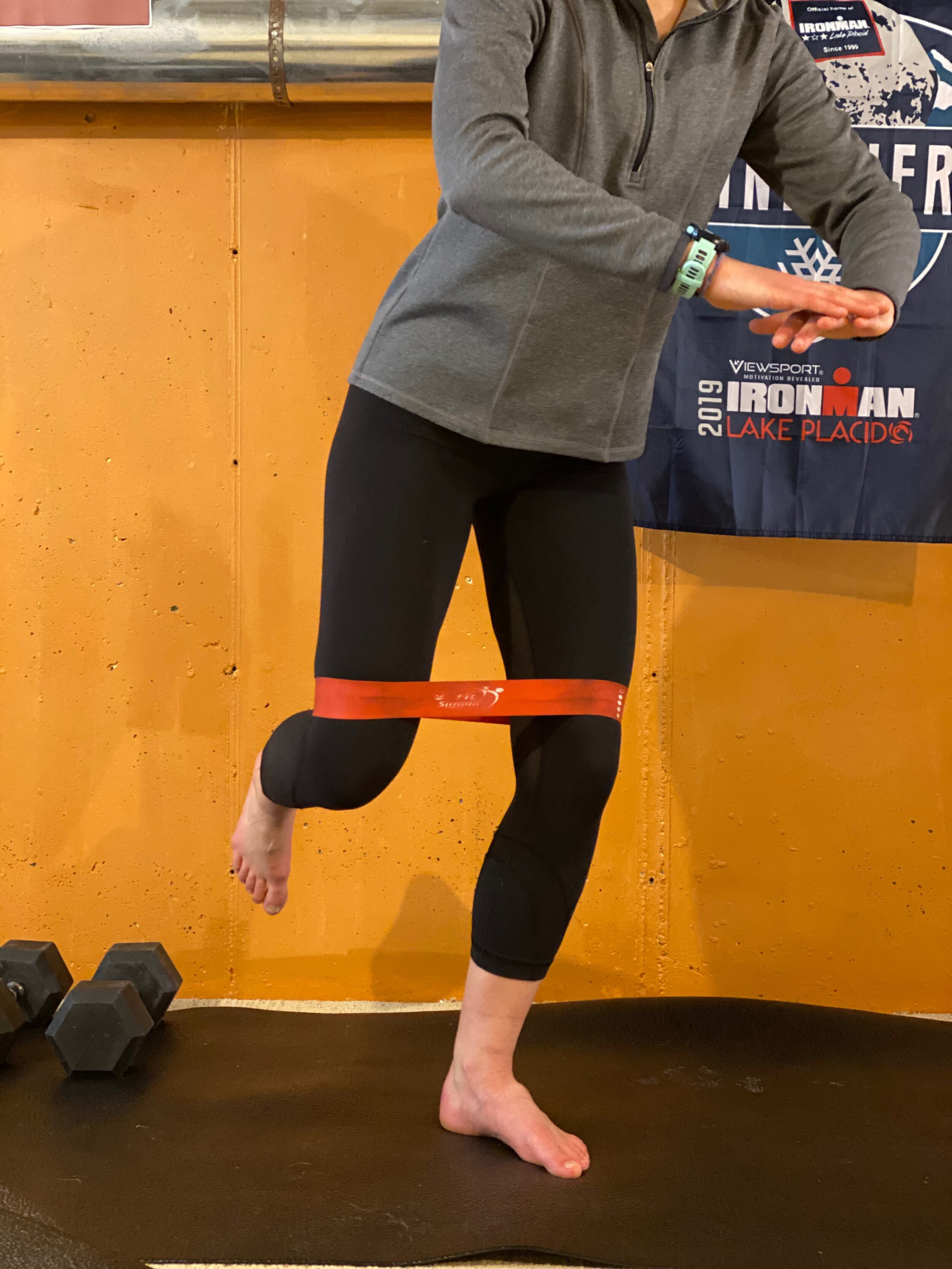

Strengthen your hips! The most important thing you can do to offset lower body injuries is to strengthen your hips. In particular, the gluteus medius is a muscle that is notoriously known for being neglected in runners and triathletes because it primarily helps with side-to-side and rotational motion, and running, cycling, and swimming are front-to-back motions. A weak gluteus medius can lead to a whole host of hip and knee injuries because the motions that the gluteus medius supports radiate all the way down each leg. I recommend purchasing a set of resistance bands and using them to do monster walks, single-leg squat balances, and clam shells for 15-20 minutes at least 2-3 times a week, preferably before running or cycling. Check out this video for a whole bunch of different exercises that you can incorporate into your weekly routine. Remember that all athletes should also be following a more formal weighted strength program like this one that strengthens muscles besides the gluteus medius for optimal injury prevention.

Warm up and cool down -- dynamically! Another habit you should try to develop is properly warming up and cooling down from exercise. Since women’s connective tissues vary in flexibility as our hormones fluctuate, warming up and cooling down can help us make sure that our muscles respond appropriately to changes in speed and effort over the course of our workout. I like to incorporate plyometric exercises like high knees, butt kicks, skipping, and lunges into my warm-up routine, especially when I’m doing high-intensity speedwork. For cool down, I’ll either swim, spin, or walk/jog at a very easy effort level until my heart rate comes back down and the lactic acid starts to flush out of my leg muscles. If you’re short on time, it’s better to cut down on your main set than to skip your warm up and cool down, and just 5-10 minutes on either end can make a really big difference for injury prevention.

Develop your form! Since women’s naturally wider hips can cause gait imbalances when we run (and even when we cycle), it’s important to actively work on improving your form. You should watch yourself run on a treadmill in front of a mirror and check to make sure that your knees aren’t touching or collapsing into each other when each foot lands. Imagine that your feet are landing on train tracks with two parallel rails rather than on a monorail. It can also help to actively pump your arms to the front and back along those same imaginary rails, in line with how your legs should be moving. Another way to work on your run form is to incorporate some speedwork into your fitness program. On long, slow runs, it’s easy to fall into bad habits that can lead to overuse injuries, but speedwork can force you to use different muscles and change the way your body moves. Even adding some 20-30 second fast-paced pick-ups to your long runs can help break bad habits. Here is a video with more details on proper running form and how to use it to improve your runs.

Fuel up! Finally, nutrition can play a large role in injury prevention. In particular, female athletes need to make sure that they are not deficient in calcium and protein. Calcium helps us build strong bones, which is especially important for women who have experienced hypothalamic amenorrhea in the past and who are at an increased risk of low bone density, osteoporosis, and stress fractures. Eating calcium-rich dairy products and/or taking calcium supplements can help you make sure that you’re getting the recommended 1,000 - 1,500 mg per day. Protein is also crucial because it helps our muscles rebuild and recover after intense exercise. Aim to get in 15-20 grams of protein after finishing your workout to kickstart recovery and help prevent muscular injuries and strains. I’m a big fan of Evolve protein drinks and Orgain protein bars for quick and easy post-workout recovery, and I’ll usually aim to have a balanced meal with more protein, carbohydrates, and healthy fats within two hours of finishing my workout.

Sports injuries that arise from crashing your bike, tripping over a curb, or twisting your ankle on the trails are hard to avoid, but you can prevent many other chronic conditions that disproportionately affect female athletes by following a bulletproof injury-prevention program that focuses on strength, technique, form, and nutrition. Achieving your A goals involves staying healthy, so consider pushing injury prevention to the top of your priority list this year!

Questions about injury prevention or anything else female-athlete related? Email me!

Resistance bands for warm up, prehab and strengthening exercises.

Part 1: The Female Endurance Athlete

When women compete and train at a high level in sports that prize a low body weight and a high lean body mass, it’s not uncommon for them to stop getting their periods. Experts estimate that this condition -- known as functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) -- may affect over 65% of female endurance runners. It’s also pervasive among triathletes, competitive swimmers, competitive cyclists, dancers, and gymnasts.

But it’s not talked about. In fact, periods have been a taboo topic in women’s endurance sports for years. That’s a big problem. Missing periods are a sign that hormone levels are off, which can lead to low bone density and stress fractures, and ultimately to infertility and other long-term health complications.

I have struggled with FHA since I started getting more serious about track and cross country running in high school. I’ve had two stress fractures in the past, and while my bone density is not critically low, it is lower than it should be for someone of my age. So after competing at the Ironman World Championships in Kona this October, I told myself that I needed a new goal: learning everything I could about FHA, getting my hormone levels back to normal, and sharing what I learned with my athletes, my training buddies, and my mentors. I took a deep dive into women’s sports physiology and came out of it with a big appreciation for optimizing women’s health in endurance sports. Here’s what I learned:

Fueling is key. The number one cause of FHA is low energy availability, which basically means that your body doesn’t have enough energy reserves to support all of the activities you do plus what it would need to carry a baby. Whether pregnancy is on your radar or not, women are evolutionarily designed to be ready to reproduce at any given time. If the body thinks that it doesn’t have enough energy in reserve for reproduction, it will shut down the menstrual cycle in an attempt to save energy for basic life functions. The problem is that this also shuts off the production of estrogen, which will stop you from building bone mass and lead to the fractures we talked about earlier. So if you have FHA, the first thing you need to do is increase the amount of fuel you’re taking in so you can convince your body that it has the energy required to carry a baby. This can be pretty hard for endurance athletes who train at a high enough volume and/or intensity that they struggle to get enough calories in to replenish what you burn. If you can’t increase your energy input any more than you already do, you may need to reduce your energy output, which brings me to point #2...

Take more rest. Another way to jumpstart a normal menstrual cycle is to reduce the volume and/or intensity of your training. This is important for flipping the low energy availability equation, as well as for reducing cortisol levels, which are another contributor to hypothalamic amenorrhea. Cortisol is a stress hormone that is secreted during exercise and other stressful situations, and while it temporarily helps you to perform your best while training, constantly high cortisol levels send a strong signal to your body that it is not a safe time to carry a baby. If you’re struggling with FHA, you should start by incorporating some intentionality into what workouts you are doing and why you are doing them to ensure that you aren’t unnecessarily piling on volume that keeps your cortisol levels high. It’s also crucial to build a dedicated off-season into the year where you dramatically reduce both the volume and intensity of your training, as well as a recovery week once a month and a rest day every week (while still fueling well during those times). Some experts suggest that women trying to recover from FHA should reduce their training to no more than 8-10 hours a week. These changes can help you build up your energy reserves and lower your cortisol levels.

Life stress matters too. Exercise isn’t the only reason behind high cortisol. Any constantly stressful situation -- work, school, moving, relationships, etc. -- can jack up your cortisol levels to the point where your cycle is impacted, and heavy exercise and underfueling will compound the problem. I’m pretty sure that I personally was under a constant state of high academic-induced cortisol during my four years as a student at Dartmouth, so it’s no wonder that I wasn’t getting a natural period even when I wasn’t training for Ironman distance races. If life stress is a problem for you, it’s important to prioritize stress management techniques, adequate sleep, and unstructured free time so you can prevent your cortisol from being even higher than it would be from training alone. (See our post on life stress here!)

Natural supplements can help. I’m not a doctor and I have no authority to give any medical advice, but I’ve had success with some natural hormone-regulating supplements for stress management (try HPA adapt) or menstrual cycle regulation (try Vitex, Femmenessence MacaHarmony, and Acetyl-L-Carnitine). They work best in the context of other fueling, exercise, and life changes and probably won’t fix FHA on their own, but they can certainly support you in moving things along as you’re working on recovering a natural period.

Birth control is NOT the answer. This one is important. Many doctors will recommend that you go on an oral contraceptive pill (OCP) if you have FHA because it forces hormone fluctuations that will cause a withdrawal bleed on a “standard” 28-day cycle. However, this is not a natural period. Medical experts who focus on FHA have come to the conclusion that birth control doesn’t actually help you rebuild bone mass, and it can give you a false sense of security because you don’t know if your body can actually support a normal cycle or not while on the pill. If you think you might have FHA, and you’re on birth control, you should talk to your doctor about these concerns and consider going off the pill to see whether you menstruate naturally. (This one hits close to home; a doctor prescribed an OCP for me when I initially stopped getting my period in high school and I stayed on it for four years. I ended up with a stress fracture twice during that time.)

Talk about it! A lot of women with FHA don’t talk about it with their coaches or teammates. But talking about it with people who are most directly involved in your athletic endeavors is the first step to developing a plan to fix FHA. If you’re working with a coach or team that refuses to support your attempts to prioritize your own health, you’re probably working with the wrong people. This was something that was difficult for me to do at first, but the outpouring of support I have received from everyone who has been looped into my journey has been really encouraging. I’ve also realized that FHA is so much more common among my broader athlete circles than I originally thought, and that has made me even more eager to keep the conversation going.

With a dedicated off-season in which I fueled well and often, set hard limits on my weekly training hours and metrics, prioritized getting enough sleep every night, started taking hormone-regulating supplements, and actively practiced stress management techniques, I ended up getting back a normal cycle within two months after not having one for almost six years. I’ve been tracking my cycle using the FitR woman app and have been modifying my training accordingly, which I highly recommend for all female athletes. While I’m only just starting to increase volume and intensity for next season -- which will most likely not include a full Ironman because grad school is busy and wedding planning is busier -- I’m confident that I’ll be able to stay on top of my health and make adjustments if anything goes awry. More importantly, I think I’ve gained a better perspective on women’s sports physiology in general, and I hope that this will help me optimize my athletes’ and teammates’ experiences in endurance sports.

The good news is that periods are finally starting to lose their taboo in the world of endurance sports. Elite athletes like Lauren Fleshman, Elyse Kopecky, Tina Muir, Sarah True, Ruth Winder, and more are speaking out about FHA and/or the more general fact that women actually have periods. So any women out there who are struggling with an irregular or missing menstrual cycle, or who have a regular cycle but feel uncomfortable about even talking about in the context of endurance sports, should know that times are changing for the better. Periods are here to stay whether we like it or not, so we might as well start talking about them.

P.S. More good news: the menstrual cycle does not actually have to be a performance limiter! I recommend Stacy Sims’ book, ROAR, for insight on how you can use your cycle to your advantage and optimize your training around fluctuating hormone levels.

Coach Katie Clayton

2019 IRONMAN World Championship Race Report

This weekend, I raced at the IRONMAN World Championship in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, after winning my age group and qualifying at IRONMAN Lake Placid in July. Initially, I was hesitant about accepting the Kona slot because I was moving across the country at the beginning of September to start a PhD program in California. To add more challenges, a month before the race I developed IT band syndrome that caused significant knee pain any time I ran more than 3 miles. With all of those factors in play, finishing the race was in doubt.

Kona is famous for its extreme heat, humidity, and winds, so even though the bike and run are slightly less hilly than IRONMAN Lake Placid, the conditions make it one of the toughest courses out there. October is Kona’s hottest month, and the swim is marked by big ocean swells, the bike by headwinds, crosswinds, and sizzling pavement, and the run by unforgiving humidity and sunshine. Most professional triathletes come out to Kona weeks in advance of the race to get acclimated to the heat, but I was busy learning about American political institutions and linear regression in dry and temperate California. I flew out to Kona with Connor the Wednesday before the race, and Jim and my dad met us there soon after.

Jim and I put together a race plan that took into account 1) the environment, 2) my semi-functional knee, and 3) the primary goal of the Kona experience, which was to have fun. Unlike at Lake Placid, there was no pressure to “qualify” for anything, and friends who had raced at Kona before reminded me that the race was just the cherry on top of a great season. We made pacing, fueling, hydration, and staying cool the top priorities. Here’s a summary of what that looked like and how it all went down:

The Swim: 1:16:02

The swim is a 2.4-mile single out-and-back in Kailua Bay. You swim about 100 yards out to some buoys that mark an “imaginary start line” in the water, tread water for a couple of minutes with your group, and then start swimming when the gun goes off (which was at 7:15 am for me). The plan was to take the swim pretty easy, sight as best as possible, and get physically and mentally prepared for the bike.

When the gun went off, it was actually pretty enjoyable. I found some people to draft behind at different points and sighted often, enjoying the tropical fish and coral underwater and the added buoyancy of the salt water. The wave start system meant that there were fewer people around me than there would have been with a mass start. Things got a little more hectic when we rounded the corner and caught up with the slower swimmers in the men’s 55+ age group, but I finished strong and felt good coming out of the water in 1:16:02, which was a little faster than what we had predicted based on my Placid swim time.

T1: 5:40

I quickly stopped at the hoses to rinse off the salt water and then headed to the women’s change tent, which was a zoo. I grabbed my bike bag and got my socks, shoes, helmet, and glasses on. A lot of people were running through transition, but I tried to just walk quickly to avoid aggravating my knee any more than it was going to be aggravated with the marathon. I made it out of there in 5:40 and was onto the bike.

The Bike: 6:14:52

The plan for the bike was to observe a *strict* heart rate cap of 150 bpm. In other words, if my heart rate went above 150, I needed to go easier. This was a pretty low cap, especially compared to my Placid effort, but the problem with Kona is that once your heart rate soars from going out too hard, it’s almost impossible to get it back down. I usually train based on power, but Jim actually told me to ignore power and base the entire bike around heart rate.

I stuck with the plan, and it was actually pretty easy to ignore power because my power meter was flickering on and off for the entire ride. My heart rate was mostly in the high 140s, and I fought to get it back down by easing off the gas any time it went above 150. The course takes you through town on a short loop, then up Palani Hill and onto the “Queen K” highway, where you bike out to mile 60 at Hawi and then back to town for a total of 112 miles. There are several sections of the course that each present different challenges: sometimes it’s intense headwinds or crosswinds, sometimes it’s oppressive heat as you bike by the lava fields, and sometimes it’s steady uphills that are usually accompanied by headwinds.

It was already hot by 8:35 am when I got on the bike, and the day just got hotter. Luckily, there were a couple of clouds that offered brief respite from the heat, and I learned early on that the best way to stay cool was to pick up an ice-cold water bottle at every aid station (approximately every 7 miles), dump the entire contents all over my head and neck, and grab a second one to drink and pour on me until I reached the next aid station. I was also trying to take in as many carbs as I could in the form of Infinit sports drink, a couple of bars, and some shot blocks. The headwinds and crosswinds picked up pretty quickly into the bike and it sometimes felt like I was either not moving forward or going to topple over, but I just stuck to my heart rate plan and ultimately made it to Hawi, where I benefited from a short but awesome tailwind on the downhill leaving the town. I battled a really tough headwind for the last 20 miles coming back into Kona, but I was glad that I had stuck to the heart rate plan and wasn’t feeling totally out of energy. Now it was time to get mentally psyched up for the big wild card: the run!

T2: 8:23

I took my time in T2 to make sure I was comfortable, because I knew there was a good chance I would be spending a long time out there for the run — especially if I had to walk. I changed socks, put on shoes, ate a stroopwafel, stopped by the porta potties, and put on my race belt, visor, and knee strap, which allegedly offers some relief from IT band pain. There were actually several women who were having various degrees of emotional breakdowns in the change tent, so I was pretty happy that I was still in good spirits after my controlled bike ride. I headed out of the tent and was off!

The Run: 4:05:03

The plan for the run was to keep my heart rate below 155, and per my doctor’s orders, “run until you can’t run anymore.” My doctor had said that I couldn’t necessarily make the injury worse by running through it in the race, but I was worried that I would be literally unable to get my leg to respond at all if the pain got really bad. I had never been more uncertain going into a run.

When I started, I actually felt pretty good. My IT band was a little stiff but I had no knee pain, and I was so happy about it that I couldn’t wipe a goofy smile off my face. I smiled all the way through the first 7 miles in town (no pain!) and enjoyed sticking ice and cold sponges down my back and dumping water on my head at every aid station. I took in a couple of gels but ultimately switched to Gatorade and flat coke because they were easier to stomach.

At mile 8 there is a big climb up Palani Hill and onto the Queen K (yes, we have to run and bike there), and that’s where it’s a little harder to keep morale up. The 17 miles on the highway and into the Energy Labs section of the run are very desolate and lonely. There are tons of spectators in town, but almost none on the Queen K. The whistling winds are punctuated by heavy breathing and wet feet pounding the pavement with a squelch.

On the bright side, I was able to run up Palani (still no pain) and continued to feel pretty good. I had to slow down my pace a little to stay under my heart rate cap, but I was doing sub-10 minute miles the whole time and I was so happy to be running for this long pain-free that I didn’t really care about the pace. I felt kind of like a ticking time bomb with a knee that could give out at any given moment, but I knew that the more miles I ran, the fewer I would ultimately have to walk.

As I ran through the Energy Labs, the sun started to set and I was getting tired. My knee was still holding up, though, so I told myself that I needed to keep running until 1) it gave out, 2) my heart rate spiked to a point where I couldn’t get it down, or 3) I literally fell over. None of those things had happened, so I pressed on. By mile 20, the sun had set over the Pacific, and the highway was pitch black. I could see the twinkling lights of the town, though, and the thought of the finish propelled me forward.

When I finally came back down Palani at mile 25, I could hear Mike Reilly’s voice and the roar of the crowds, and I started to get excited because I knew that even if my knee gave out now, I would still be able to walk, crawl, or even roll across the finish line. By some miracle, it continued to cooperate, and I picked up the pace for a smiling sprint down the finish chute. The crowd was roaring, the lights were bright, and as I crossed the finish line I heard those magic words: “Katie Clayton, from Stanford, California…Katie, YOU ARE AN IRONMAN!”

Finish: 11:49:57, 14th in AG, 5th American

The 2019 IRONMAN World Championship was not my fastest race, but it represented my best-ever execution of a race plan. I was enjoying myself for almost the entire time, I ran the whole marathon, and I didn’t end up in the med tent. And hey -- if the advice to “have fun” lands me with 14th in the world and 5th American in my age group, I’d like to think that I have a whole lot more untapped potential that’s just waiting to make its debut. - Coach Katie

Katie Clayton 2019 IRONMAN World Championships - Kona, HI

2019 IRONMAN Lake Placid Race Report -- Chris Klein

Expectations and Pre-Race Thoughts

Ironman Lake Placid (IMLP) had the distinction of being both my A-race and my first race of the season. After taking a year off from triathlon, I had been feeling anxious to get back into race mode. I was also excited to see the results of actually training for a triathlon. Coming off a collegiate swimming career, I had previously relied on endurance from distance training and natural fitness to get me through triathlons. This was my first time working with a coach, and I knew that my training over the last seven months was well thought out. I was ready.

The Plan

Swim. Approximately 1:00 – 1:05 on the swim. Be aggressive, but do not expend any energy. If possible, find someone at a similar or slightly faster pace and draft off them to conserve energy. Keep the cable in sight. Use the swim to get the pre-race jitters out of the way.

Bike. Maintain a normalized power of 160-170 for the bike. Keep heart rate under 150 bpm, but ideally closer to 140 (or lower). Keep head position steady. Eat every 20 minutes, and drink at least every 10.

Run. Cap HR at 155, but try to stay between 140-150. Do not blow out the energy in the first few miles – it’s a long race. Maintain hydration. Hope that the leg cramps decide not to show up today.

Nutrition. I used Science in Sport (SiS) electrolyte powder, carbohydrate bars, and gels.

Swim

Although my goal swim was in the low 1:00 mark, I placed myself in the sub 1:00 group. IMLP’s swimmers have a reputation of seeding themselves faster than they will actually finish, and so I wanted to get ahead of any athletes who were a bit…overeager. Additionally, I wanted to get ahead of the mass pack which would no doubt involve a fair amount of aggression as swimmers would jockey for a spot on the cable.

The first 1000 yards went off like any other open water swim. There was a fight for position during the first 500 yards as the lead bunch formed into a pace line. Rounding Turn 2 (~1000 yds), I made my only ‘mistake’ of the swim when I got too comfortable with the reduced need to spot and overshot the turn by about 20 yards. Not a big deal, but it was a fitting mistake considering that a sense of direction was never my strong suit.

I was able to find a swimmer slightly faster than me to draft behind for the second 1000 yards. This was my strategy going into the swim, and I was able to stay on his feet for most of the straightaway. I was surprised by how many people were swimming off the cable – some by over 25 yards to the left. Yes, this would reduce the traffic they would encounter, but swimming away from the pack seemed unnecessary given that we were still on the first lap and had clear, open water in front of us.

Lap 1: 29:14

The first half of the second loop went about as well as the second half of the first loop. Although I continued to draft off the guy ahead of me, we were caught by a chase pack which had engulfed the two of us by buoy 5 (~2900 yds). For context, the IMLP swim course is a rectangle with eight yellow buoys on the way away from the start, two red buoys to mark the turns at the other end of Mirror Lake, and eight orange buoys on the way back to shore.

By the time our group rounded Turn 2 and was on the homestretch, I encountered probably the hardest challenge of the swim: the slower age groupers. The open water quickly devolved from an organized pace line to an ‘every-man-for-yourself’ maelstrom. Sighting was required, but mainly to look out for other swimmers rather than check if we were on course. I had to figure out who was ahead of me, if there were gaps to shoot, and if it was easier to swim through or swim around the athletes ahead of me. As rushed as it may seem, that chaos is one of my favorite things about open water swimming – it requires more thinking and aggression than swimming in a pool.

Before long, I saw an orange buoy with an “8” followed by a red buoy with a T3, meaning I had reached the end of the lap. I was feeling really strong, not out of breath, but strong. The race was on.

Lap 2: 30:14

Total Swim: 59:14. 1:00 goal complete.

Transition #1

The transition involves a long-ish run (at least a quarter mile) from Mirror Lake to transition. This was the first time I had ever used a wetsuit stripper (and the first time I had ever used a wetsuit), and so the process of being told to lie down on the ground as a volunteer yanked my wetsuit off my legs in one smooth motion was interesting, but efficient. I entered transition, grabbed my bike gear bag, and ran into the changing tent.

The volunteers were great, and I was fortunate to be in the changing tent with relatively few athletes (most were still in the water). While I was putting on my socks, shoes, and rubbing some chamois cream on my thighs, the volunteer was getting my glasses, helmet, and gloves ready to go. Transition times were significantly slower than every other triathlon I had previously done. What I thought was a really slow transition was actually 5th in my AG. Taking an extra minute or two in the changing tent doesn’t mean too much in a 10+ hour race.

Transition 1: 6:03

Bike

I read a sentence on a blog post somewhere which stuck with me throughout my longer training rides: “In Ironman, do the bike you should, not the bike you could.” I knew it was important to keep a consistent pedal stroke and monitor my power output, but I also wanted to ride a race I could be proud of. This meant that I would race to my plan: not an easy ride, but not an over-aggressive ride that would destroy my run.

The climbs out of Lake Placid are inconspicuously long, and I’m thankful that I came out in June to practice the course as I knew to take this section slow and smooth. I saw a few cyclists absolutely pounding the opening hills, and I remember thinking that they were insane – we still had 9 more hours of racing left!

The downhill screamer to Keene is one of my favorite parts of the course. I hit a new speed record for the year, and it was nice to have a section where I could bank some free miles. Then came the flats to Wilmington and soon, the severely underrated climb out of Wilmington. Again, some bikers were flying up the hill looking like they were cranking more watts than a professional cyclist on a hors catégorie mountain. Later, I saw several of them walking on the marathon…

Even on the long climb back to Lake Placid, I was feeling good – much better than I was expecting. My power was at my goal watts, my body was feeling fine, and I was hitting my nutrition. When I rode into Lake Placid, I looked down at my computer to mark the lap and saw a 2:54 – more than 20 minutes faster than my anticipated lap split (3:15). Rather than excitement, this actually caused a good deal of anxiety starting the next lap, and I worried I had killed the rest of my race by taking the first lap too aggressively. But I was still feeling strong, I was having fun, and the crowds were cheering me on through town. Riding down Mirror Lake Drive, I pounded my chest and yelled with the crowd, rejuvenated by the energy of the spectators lining the streets. I saw my parents, grandparents, and a friend from college who came up to watch me race, all recognizable by their matching blue shirts with a picture of me printed on the front. The anxiety quickly disappeared.

Lap 1: 2:54

Chris Klein IRONMAN Lake Placid family t-shirt

But sure enough, the problems started on the second lap. Earlier than in my training runs, my body started to reject the carbohydrate bars I was eating, and my electrolyte drink seemed less and less appealing with every sip. I started missing scheduled eating and drinking periods. On what began as a cloudy day, the sun started to break through the clouds, and brought with it rising temperatures on the exposed roads.

Finally, on the climb passed Whiteface, I cracked. My quads cramped up several times, requiring me to pull over to the side of the road and try to massage them out. But worse than the cramps, massive headwinds, absent on the first lap, hampered any forward progress I was making when I would resume my rides. My two training partners, Matt and Katie, both passed me as I was trying to massage out a cramp, and, truth be told, I took relief in seeing familiar faces. Although I appreciated the “are you ok?’s” from concerned cyclists as they rode passed me parked on the side of the road, it was a little demoralizing recognizing that I still had to make it to Lake Placid in order to even start the run.

After finally getting back on my bike, Mile 100 is where I hit my low point. I was well aware that mental toughness was necessary to finish this race strong, but I was not expecting to have my attitude tested so early in the day. After what seemed like an eternity, I finally got to the top of the Northwood Road climb (the short, sneaky climb after the three bears) and enjoyed the coast to transition. Even with the pain, I still finished the lap ten minutes over my anticipated lap split.

Despite all of the negative emotions mentioned in the previous three paragraphs, I was still having fun. In a sense, nothing was awry…yet. Ironman is a hard race, plain and simple. I knew I was going to struggle with the bike, and although it wasn’t perfect, I made it. Every problem I encountered, I anticipated and had a plan. Race day preparation is an undervalued benefit of having a coach, and as a result, panic mode never set in. Instead, I was ahead of schedule, I was faster than my training rides, and I was still feeling strong enough to run a marathon. Furthermore, I wasn’t hurting alone. Pictures may speak louder than words, but facial expressions in Ironman are an open book for describing how an athlete is feeling. Based on the emotionless faces and glassy, empty eyes, my pain was in good company.

Lap 2: 3:23

Total bike: 6:17. 6:30 goal complete

Transition #2

After crossing the dismount line and handing my bike off to a volunteer, I decided that the path to the changing tent was more deserving of a walk than a run. My legs were hurting, and all I could think about was getting out of my biking shoes. In the tent, I took off my helmet, swapped my socks and shoes, threw a bag of sodium gels in my pocket, quickly downed some fluids, and headed off on my run. Just like in Transition 1, I thought I was moving slowly in T2, but my time was actually above average for age groupers.

Transition: 5:43

Run

Despite all of the pain I had felt during the last 20 miles of the bike and heading into transition, I actually felt great for the start of the run. I set my watch to focus solely on my heart rate. I used the opening downhills to lengthen my stride and stretch out my quads and calves. I was moving, and with my speed came energy – I was back to having fun!

One aspect of the race I haven’t touched on too much yet is the crowds. I’ve never seen more support in a race than from the fans and volunteers in Lake Placid. Coming out of transition, I heard more cheers of “let’s go” and “come on, Chris” than in all of my previous races combined. It felt very personal, like they were cheering for me instead of the usual casual clap as spectators wait for their athlete(s) of focus. There were also the fans who tried to be more…unique. The spectator on the ski jump hill at Mile 2/9/15/22 who high-5’d everyone with Facebook foam fingers. The fraternity squad at Mile 1/10/14/23 who cheered for everyone while parading around in their underwear. The aisle of fans on Mirror Lake Drive who tried to motivate the nutrition-depleted runners as they “death marched” to the completion of their first lap. Their energy was contagious and set a new standard that I fear will never be matched by another race nor another crowd.

But outside of Lake Placid and down Riverside Drive (Miles 3-9 and 16-22), spectators could not easily watch the race and the non-athletes were limited to the volunteers working at aid stations and the medical tent. The lack of cheering fans shouting encouragement diminished the environment to the sight of expressionless runners trying to get to the next aid station and the sounds of running shoes shuffling down the road. The course, on the other hand, was shaded and pretty with the road running adjacent to a small stream.

Early in the run, I was still feeling strong. I was holding around 8:45’s but my HR was starting to rise, still within the 150 range. Many athletes had started walking (my assumption being those who tried to overdo the bike), and truth be told, the number of runners I passed in those opening miles was encouraging. I linked up with another runner who was holding my pace and we chatted for the next 5 miles until the run turnaround when the exhaustion finally caught up to him and he resorted to the ‘death march.’

For me, the struggle began around Mile 8. My heart rate had started to creep into the 150s and low 160s, and even though I eased my pace to 9:30’s, I had a hard time getting my heart rate to come down. I spent the aid stations trying to get as many calories and fluids as I could into my system – water, Gatorade, bananas, chips and pretzels, more Gatorade, more water, ice to hold in my hands and mouth – but my irregular nutrition patterns on the bike had started to wear me down. Mile 9 was the ski jump hill climb, and after walking up the hill I found I couldn’t engage my feet to run again. I was stuck. Then came the cramps: calves, quads, hamstrings, even my groin. My state could best be described by my stop at special needs (Mile 12) when I had a seven-year old volunteer named Gio and his dad help me change my socks. The cramping in my legs was so bad that I couldn’t move/engage the small tendons and muscles without my body wrenching in agony. One of my favorite pictures taken at Lake Placid was on the run where it looks like I’m laughing and shrugging my shoulders. In reality, my dad had yelled to me, “You’re almost there!”, to which I responded, “Dad, what are you talking about? I’m shuffling like a tap dancer, and I still have a half marathon to go!”

Lap 1: 2:07

The only aspect of the race for which I did not prepare was the amount of GI distress that I would encounter, and I do not think I could have prepared for that type of pain. From the start of the second lap, I felt sick, and I knew that throwing up would only deplete me of the electrolytes my body had yet to process and desperately needed. At Mile 14, I found Coach Jim on the course and even asked him if I should throw up – he advised against it. After 9.5 hours of work, my body was fighting back, and I was about to head back out to the isolation of Riverside Drive.

As it turns out, a bathroom break was really what I needed at the time, and when I came out of a porta potty at Mile 15, I saw Matt about 50 feet ahead of me looking like he was in a very similar condition as I was. We made a pact to finish the race together, and our pacing switched to three minutes of running/jogging/shuffling followed by one minute of walking. Between the GI distress and the ever-present leg cramps, the hurt was real. We both knew the key to finishing was to keep moving, even if it meant a slow walk. Looking around us, the ‘death march’ present on the first lap had evolved to a ‘death march of zombies,’ but the three minutes of running/consistent movement and the mental relief of running with a training partner gave me the strength to keep going. Around Mile 21, Matt and I were joined by Julie Smith, another Upper Valley triathlete, and the motivation and positive encouragement present in the Upper Valley progressed the time, both physically and mentally.

Chris Klein, Julie Smith & Matthew Goff - IRONMAN Lake Placid run

As we climbed back into Lake Placid, the crowds brought us to the finish line. Spectators lined Main Street and Mirror Lake Drive, and the high-5’s and screaming fans were moving. My legs were starting to give out from the cramping, and Matt waited for me to briefly massage them out while Julie finished her own race. From the final aid station, Matt and I decided to make one final, consistent run to the finish line.