ATHLETE RACE AND TRAINING BLOG

A place to report, share and learn from fellow athletes

Contraception Choices for Female Athletes

For anyone, choosing the right method of birth control presents a challenge. This challenge becomes even greater for female endurance athletes, as different methods have different pros and cons related to health and athletic performance. I’ve spent the last couple of months learning about the pros and cons of various contraceptive methods as I’ve debated whether to switch up my routine, and this post summarizes what I’ve learned about contraception and its effects on athletic performance. I should caveat this post with the disclaimers that (1) I’m not a doctor, (2) I have received no formal medical training (although this post has been checked and edited by multiple nearly-doctors and female badasses in my corner—you know who you are and thank you!), and (3) contraception choices are very individual-specific and have no “right” answers. You should absolutely do your own research and make an informed decision about what is best for you!

Combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs): OCPs deliver estrogen and progesterone systemically (i.e., throughout the body). A big pro is that it is easy to stop taking them for any reason without going through a medical procedure (such as IUD removal). However, some important cons for female athletes are that OCPs have been linked to worse athletic performance outcomes, including decreased VO2 max, higher oxidative stress, and/or decreased ability to adapt to intense training. This is largely because estrogen changes the body’s ability to hit intensities and recover from stress. Since OCPs pump a large amount of estrogen and progesterone through the body throughout the month (approximately 6-8 times the amount we produce naturally), women are effectively in a continuous high-hormone state and miss out on the natural fluctuations in hormones that generally allow them to hit higher intensities in the first half of their cycle (the follicular or low-hormone phase). When female athletes use OCPs, experts estimate that around 11% of their performance potential is left on the table.

Moreover, an important misconception about OCPs is that they give you a natural period. There is a “withdrawal bleed” associated with the fourth week of the cycle (a placebo pill), but this bleed is not a normal period and does not indicate that a woman is cycling naturally on her own. This is why using OCPs for female athletes experiencing hypothalamic amenorrhea (stopped periods) is generally a bad idea (unless it is being used to treat other underlying health conditions such as endometriosis, PCOS, chronic pelvic pain, menstrual migraines, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, ovarian cysts, acne, or hyperandrogenism), because it masks the underlying problem of energy deficiency and may not fix the associated declines in bone density and other negative health outcomes.

Note: Other options that include systemic hormones are the patch, the DePo-Provera injection, and the implant. There is less research on how these methods impact female athletes and endurance training given their often less-desired side effect profile, but there is reason to believe that they have similar systemic effects on performance.

Hormonal IUDs (in a class known as long acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs); brands include Mirena, Kyleena, Liletta, Skyla, etc.): Hormonal IUDs (intrauterine devices) are small, T-shaped devices that are inserted vaginally and placed directly inside the uterus by a medical provider. Hormonal IUDs release small amounts of the hormone progestin (levonorgestrel) into your body, which prevents pregnancy by stopping sperm from reaching and fertilizing eggs via changes to cervical fluid that inhibit sperm transport and changes to the endometrium that inhibit implantation, among other mechanisms. Pros are that they are highly effective, can be used for 5-7 years, and do not release estrogen into the body, so they are not associated with the same negative effects on athletic performance as combined OCPs. By contrast, research suggests that they mimic a natural cycle and might even be beneficial at reducing PMS-related performance declines in the late luteal phase. Fertility also usually resumes immediately after IUD removal, while it can take longer to resume when coming off of combined OCPs and other systemic methods.

However, important cons for female endurance athletes who are training at a high level and/or are worried about potential energy deficiency are that they can lead to stopped periods, which eliminates a key indicator that an athlete is handling fueling, training, and stress appropriately. (Note: This can also be a pro for those who are not worried about energy deficiency and prefer the logistical benefits of not dealing with a period.) The differences between hormonal IUD brands are the size (for example, Mirena and Liletta are slightly larger than Kyleena and Sykla) and the amount of hormones that are released into the body. For the Mirena, for example, which has 52 mg of levonorgestrel, about 20% of women will stop getting their period after a year, and for the Kyleena, which has 19.5 mg of levonorgestrel, about 12% will stop their period. There is currently no way to predict how a woman’s cycle will react to a hormonal IUD, but it’s important to keep in mind that IUDs can be removed. It also takes people a few months to adjust to the influx of hormones that come from the IUD, so cycles can be irregular and many people experience spotting as they adjust. People usually have their new normal cycle by 3-6 months.

Finally, IUD insertion can also be painful. That said, there are a variety of things you can do to mitigate this, including asking for lidocaine-prilocaine cream, taking misoprostol prior to insertion (though the data are mixed on whether this helps), using ibuprofen for cramping, and scheduling your training around the insertion procedure to give your body a chance to rest and do its thing. Many women agree that a small amount of discomfort is worth it for the peace of mind that they will not get pregnant.

Progestin-only mini pill: For women who do not want the systemic effects of estrogen and progesterone but also do not want an IUD, there are progestin-only oral contraceptives. These pills are thought to have similar non-effects on athletic performance as an IUD and are easier to stop taking for any reason, although they are not localized.

Copper IUDs (also a LARC; most common brand is Paragard): The copper IUD (Paragard) is a hormone-free IUD that works by creating a toxic environment in the uterus for sperm. It is one of the only hormone-free birth control options for women (other than medical sterilization and FAM) and is highly effective. It can also be inserted as an emergency contraceptive method, and is effective for up to 10 years. A big pro is that you will still get a period while using a copper IUD (allowing you to use your period as a guide for health and performance), but a con is that periods can generally be heavier or more painful for several months after insertion. Like with hormonal IUDs, the insertion procedure can also be painful, and the copper IUDs are the largest in terms of size (although they are still objectively small and do not interfere with athletic performance or sex).

Fertility awareness method (e.g., Natural Cycles): Some people prefer to avoid hormones and devices altogether and will use the “fertility awareness method” to track their cycles and prevent pregnancy. By tracking indicators like basal body temperature, cervical fluid consistency, and cervical shape, you can identify with some certainty what phase of the menstrual cycle you are in and avoid unprotected sex during your fertility window, which can be about 7-10 days for most people. Apps like the Natural Cycles app have made tracking easier, and many women enjoy learning more about their own physiology throughout the process. However, this method does take a lot of effort and tracking behaviors, and it rules out unprotected sex for several days in a given month, which many people dislike.

My experience

My main considerations related to choosing a birth control option were the following: (1) I probably want to get pregnant eventually, but not anytime soon, and I want to have high confidence that I won’t get pregnant now; (2) I do not want birth control to negatively impact my athletic performance; and (3) I like to use a natural menstrual cycle as a regular indicator that my body is handling stressors, training load (energy output), and fueling (energy input) appropriately. As someone who experienced RED-S (relative energy deficiency in sport) in college (you can read more about that here), point #3 was particularly important to me.

For all of these reasons, not being on birth control and tracking my cycle naturally was the right choice for me for a while—that is, until I confronted the reality that condoms aren’t perfect and had to take plan B (an emergency contraceptive). While that was ultimately the right decision, it was an objectively bad experience for me for multiple reasons (happy to elaborate for anyone in a similar position who is curious), and I was confident that I didn’t want to have to take plan B again unless absolutely necessary. So that meant that I needed to find a new birth control solution that would give me greater certainty that I could avoid an unwanted pregnancy.

I was fairly certain that all methods that featured systemic (non-localized) doses of estrogen and progesterone (including OCPs, patches, injections, implants, etc.) were off the table for me because of their potentially negative consequences on athletic performance. That left me with hormonal IUDs, a copper IUD, or the fertility awareness method. FAM seemed like a lot of work to do correctly, and I was worried that I would not feel as confident about the effectiveness of the method as I would with an IUD.

The copper IUD was attractive to me because it contains no hormones, but I was concerned about the performance effects (and logistical nuisance) of potentially heavier, longer, and more painful periods—especially when I’m well on my way into a big IRONMAN build. I actually sent Colleen Quigley—an Olympic steeplechaser-turned-triathlete and social media influencer who has been amazingly vocal about her copper IUD experience—an Instagram DM asking for her thoughts, and she reiterated that she loves the copper IUD now but would recommend getting it placed during an off season rather than during peak training, which wouldn’t have been an option for me until the fall.

For the hormonal IUDs, my main hesitation was the idea that I could end up not getting my period, which would make it harder to have an objective indicator of overall health and balanced energy input and output. Ultimately, I decided to go with the Kyleena, one of the two lower-dose hormonal option (my OB-GYN told me that the Skyla, which is technically the smallest and lowest hormone dose, is being phased out of use because it’s not very different from the Kyleena and only lasts for three years before it has to be removed or exchanged). I then learned more about ways to keep tabs on your cycle even without having your period as an indicator, including:

Keeping track of other menstrual cycle-related symptoms, including patterns in resting heart rate or heart rate variability, breast tenderness, feeling more bloated (a result of fluid retention), mood swings, sex drive, cervical fluid, etc.

Keeping track of symptoms related to energy balance, including weight loss, mood swings (especially anxiety/depression), persistent illness, injuries, sleep quality, performance declines, always feeling cold, etc.

Optionally, getting bloodwork done to measure estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone to let you know whether you are in the follicular or mid-follicular phase.

The insertion procedure itself was not fun at all, which is another important potential con for people considering getting an IUD. I had heard that the Kyleena insertion might be the least painful (compared to the Mirena or the Paragard) because it is the smallest in size, but holy hell it was an experience. I took misoprostol the night before the procedure, which is theoretically supposed to make insertion less painful by dilating the cervix. I also took ibuprofen about 30 minutes before the procedure and throughout the day afterwards, and I had planned a very easy training day. Even so, my OB-GYN had to do the insertion twice because according to her I have “the strongest pelvic floor she has ever seen” (humble brag, I know) and it hurt a lot both during and afterwards. But I woke up the next day feeling a lot better and have only experienced mild cramping and other PMS-like symptoms in the days following, and have mostly resumed normal training.

I’ll have to do a follow-up post in a few months to definitively weigh in on how the IUD did or did not affect my experience as a female athlete, but for now, I stand by the decision that I made. I know that my odds of getting pregnant are extremely unlikely, I am confident that the IUD is unlikely to negatively impact my performance, and I have a plan for how to stay on top of health indicators even if I end up in the minority of people with an IUD that do not get a period. I also feel empowered for making an informed decision. Special thanks to the many amazing friends, doctors, and other important women in my corner who shared their experience, expertise, and insight to help me figure this out—girl power!

Some resources if you want to learn more about contraceptive methods and pros/cons:

The Effects of Contraception on Female Athletes’ Performance

The Fifth Vital Sign: Master Your Cycles & Optimize Your Fertility

A few favorite social media follows on topics related to contraception/ the menstrual cycle and female athletes:

Part 2: The Female Endurance Athlete

In the second installment of our three-part series on female endurance athletes, I’d like to talk about something that all athletes like to pretend doesn’t exist until it stops them in their tracks: injury. While sports injuries are absolutely not a women-only problem, there are certain aspects of female physiology that make us more prone to imbalances that, when ignored, can lead to ACL tears, IT band syndrome, patellofemoral syndrome, and more.

How do women differ from men in our propensity to certain sports injuries? For starters, women’s muscle stretch reflex changes over the course of the menstrual cycle, which means that our connective tissues are less flexible at certain hormone levels than others. Second, because we are evolutionarily designed to bear children, women’s hips are naturally wider than men’s, which means that we are more likely to run with a knock-kneed gait and excessively overpronate. Third, women are anatomically smaller than men, which means that our joints and muscles are more compact and can create excessive friction when they rub together during activity. Finally, because inadequate estrogen due to menstrual cycle imbalances is a common problem among female athletes, low bone density tends to be more common among women than men, and this leads to a higher instance of stress fractures (see Part 1 in this series for more details on how to reduce the occurrence of stress fractures in female athletes).

Does all of this mean that we should give up on participating in sports? Of course not! But as women, we need to take extra care to make sure that we work on core strength development and mobility work that can counteract the anatomical traits that may be working against us. Here is a list of things you can do to help prevent some of the most common injuries in female endurance athletes:

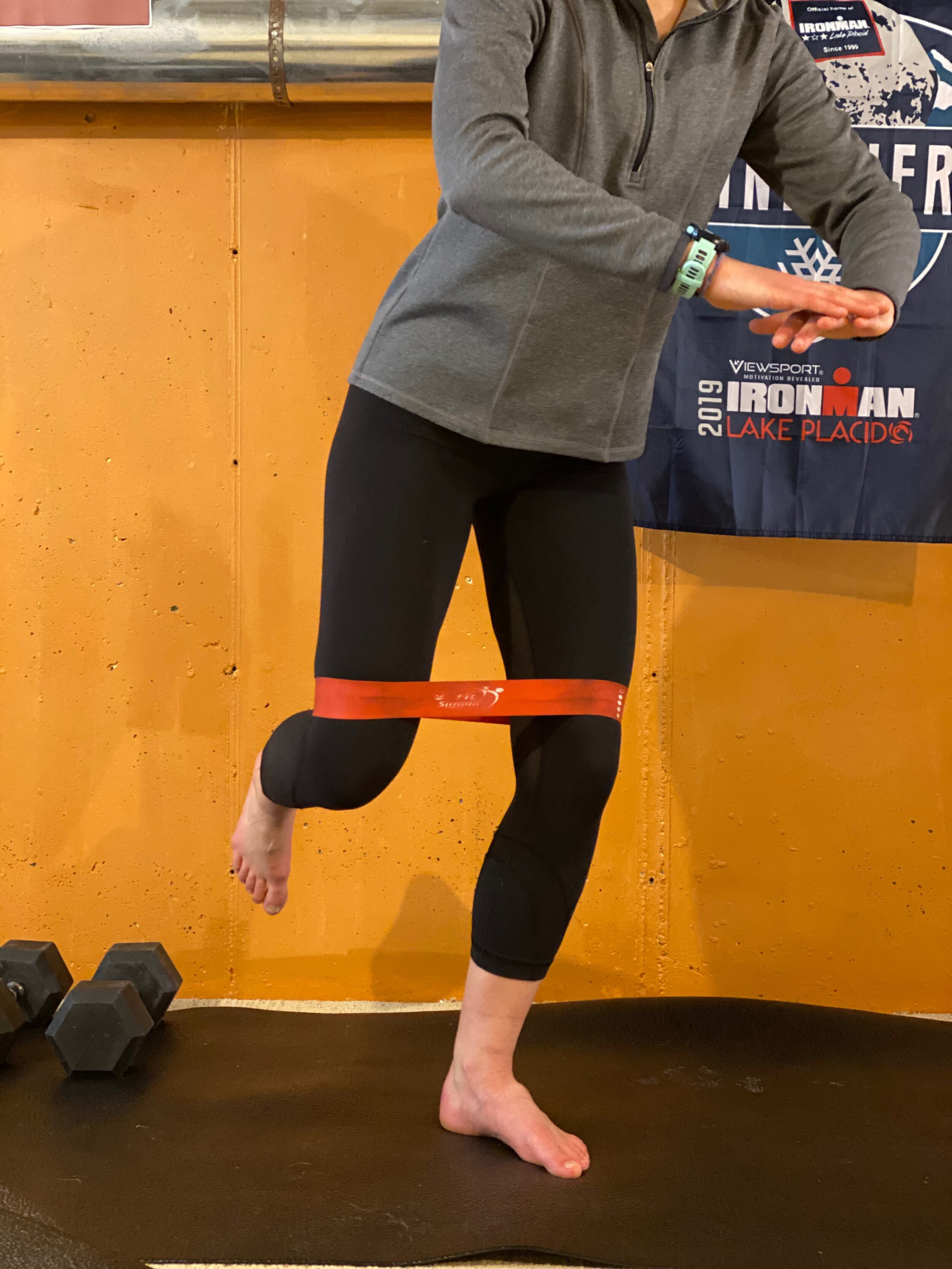

Strengthen your hips! The most important thing you can do to offset lower body injuries is to strengthen your hips. In particular, the gluteus medius is a muscle that is notoriously known for being neglected in runners and triathletes because it primarily helps with side-to-side and rotational motion, and running, cycling, and swimming are front-to-back motions. A weak gluteus medius can lead to a whole host of hip and knee injuries because the motions that the gluteus medius supports radiate all the way down each leg. I recommend purchasing a set of resistance bands and using them to do monster walks, single-leg squat balances, and clam shells for 15-20 minutes at least 2-3 times a week, preferably before running or cycling. Check out this video for a whole bunch of different exercises that you can incorporate into your weekly routine. Remember that all athletes should also be following a more formal weighted strength program like this one that strengthens muscles besides the gluteus medius for optimal injury prevention.

Warm up and cool down -- dynamically! Another habit you should try to develop is properly warming up and cooling down from exercise. Since women’s connective tissues vary in flexibility as our hormones fluctuate, warming up and cooling down can help us make sure that our muscles respond appropriately to changes in speed and effort over the course of our workout. I like to incorporate plyometric exercises like high knees, butt kicks, skipping, and lunges into my warm-up routine, especially when I’m doing high-intensity speedwork. For cool down, I’ll either swim, spin, or walk/jog at a very easy effort level until my heart rate comes back down and the lactic acid starts to flush out of my leg muscles. If you’re short on time, it’s better to cut down on your main set than to skip your warm up and cool down, and just 5-10 minutes on either end can make a really big difference for injury prevention.

Develop your form! Since women’s naturally wider hips can cause gait imbalances when we run (and even when we cycle), it’s important to actively work on improving your form. You should watch yourself run on a treadmill in front of a mirror and check to make sure that your knees aren’t touching or collapsing into each other when each foot lands. Imagine that your feet are landing on train tracks with two parallel rails rather than on a monorail. It can also help to actively pump your arms to the front and back along those same imaginary rails, in line with how your legs should be moving. Another way to work on your run form is to incorporate some speedwork into your fitness program. On long, slow runs, it’s easy to fall into bad habits that can lead to overuse injuries, but speedwork can force you to use different muscles and change the way your body moves. Even adding some 20-30 second fast-paced pick-ups to your long runs can help break bad habits. Here is a video with more details on proper running form and how to use it to improve your runs.

Fuel up! Finally, nutrition can play a large role in injury prevention. In particular, female athletes need to make sure that they are not deficient in calcium and protein. Calcium helps us build strong bones, which is especially important for women who have experienced hypothalamic amenorrhea in the past and who are at an increased risk of low bone density, osteoporosis, and stress fractures. Eating calcium-rich dairy products and/or taking calcium supplements can help you make sure that you’re getting the recommended 1,000 - 1,500 mg per day. Protein is also crucial because it helps our muscles rebuild and recover after intense exercise. Aim to get in 15-20 grams of protein after finishing your workout to kickstart recovery and help prevent muscular injuries and strains. I’m a big fan of Evolve protein drinks and Orgain protein bars for quick and easy post-workout recovery, and I’ll usually aim to have a balanced meal with more protein, carbohydrates, and healthy fats within two hours of finishing my workout.

Sports injuries that arise from crashing your bike, tripping over a curb, or twisting your ankle on the trails are hard to avoid, but you can prevent many other chronic conditions that disproportionately affect female athletes by following a bulletproof injury-prevention program that focuses on strength, technique, form, and nutrition. Achieving your A goals involves staying healthy, so consider pushing injury prevention to the top of your priority list this year!

Questions about injury prevention or anything else female-athlete related? Email me!

Resistance bands for warm up, prehab and strengthening exercises.